Question: What rights and freedoms do you think the government should protect?

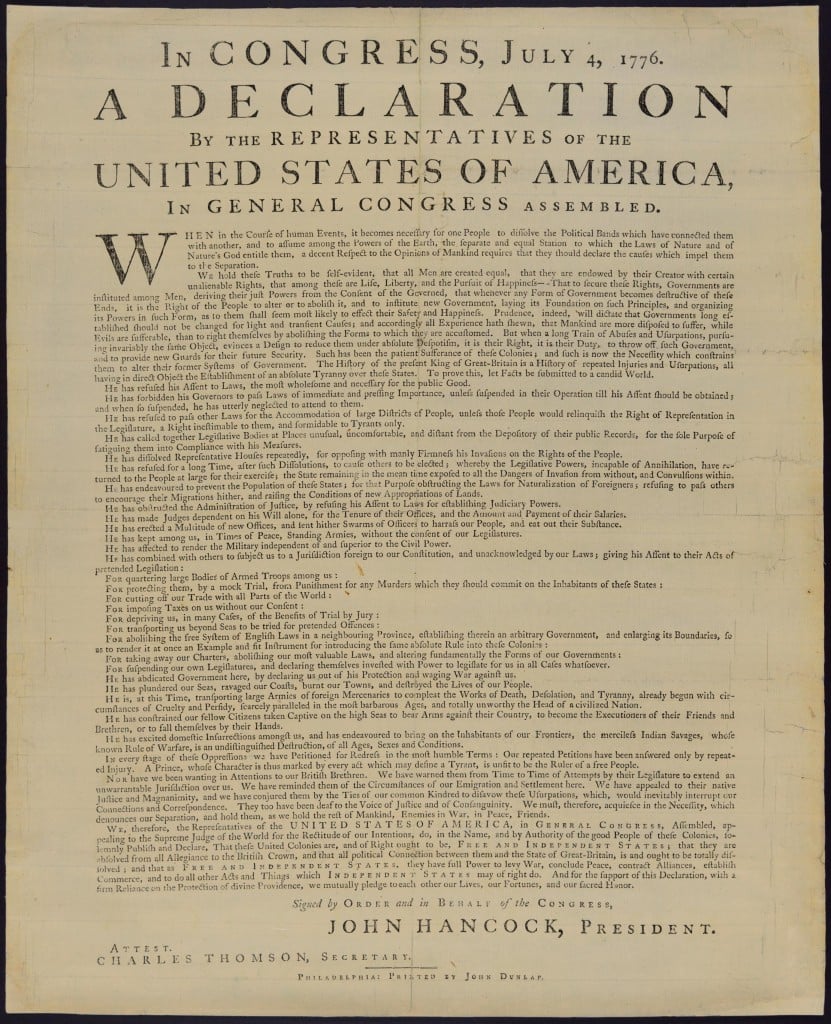

The Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies, then at war with Great Britain, regarded themselves as 13 newly independent sovereign states, and no longer a part of the British Empire.

The Declaration justified independence by listing colonial grievances against King George III, and by asserting certain natural and legal rights, including a right of revolution. These ideas were based on Enlightenment philosophy, particularly John Locke’s theory that government power derived from the consent of the governed.

Check out a great warm up video here.

This video has a great introduction by Morgan Freeman on the context and impact of the Declaration of Independence. It also features a complete read-through of the document by a cast of Hollywood movie stars. However, the read-through is not quite as dramatic as I thought it would be…it kind of starts to drag when they get to the list of 27 grievances. I recommend just showing the introduction.

This video is from the John Adams miniseries. It gives a nice context on the debate in the Continental Congress (The reading at the end is MUCH more interesting and dramatic…it doesn’t include the list of grievances).

An abridged Declaration of Independence (full text version)

PREAMBLE

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

*Translation – This document will explain why we want independence!

RIGHT OF PEOPLE TO CONTROL THEIR GOVERNMENT

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

Questions: Describe the “unalienable rights” in your own words. What rights and freedoms do you have now that you think the government should protect? Where does government get its power? What if a government does not defend the rights of its citizens? What are some groups that were not treated equally during colonial times?

LIST OF 27 GRIEVANCES (COMPLAINTS AGAINST THE BRITISH KING)

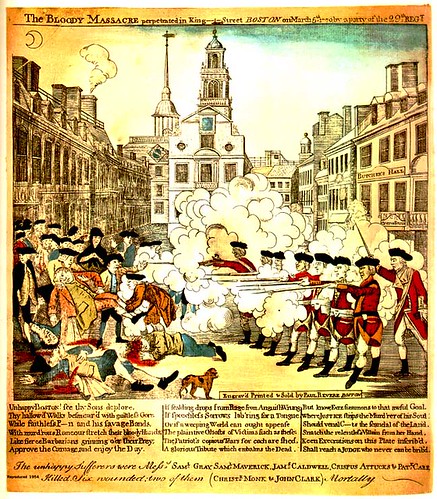

- Abuses 1 – 12 abuses involve King George III’s establishment of a tyrannical authority in place of representative government. King George III rejected legislation proposed by the colonies, and replacing colonial governments with his appointed ministers. The King is a tyrant, because he keeps standing armies in the colonies during a time of peace, makes the military power superior to the civil government, and forces the colonists to support the military presence through increased taxes.

- Abuses 13 – 22 describe the involvement of Parliament in destroying the colonists’ right to self-rule. Legislation has been passed to quarter troops in the colonies, to shut off trade with other parts of the world, to levy taxes without the consent of colonial legislatures, to take away the right to trial by jury, and to force colonists to be tried in England.

- Abuses 23 – 27 refer to specific actions that the King George III took to abandon the colonies and to wage war against them. For example, the American sailors were regularly kidnapped and forced to serve in the British navy.

Question: Which grievance do you consider the most important?

COLONIES ARE DECLARED FREE AND INDEPENDENT

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Questions: What powers do the new United States have? Who do you think was the intended audience of this declaration (name as many people or groups as you can)?

Reflection

These are GREAT ideas from the Declaration of Independence:

- “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

- A government is a contract with the citizens. People give up some of their freedoms, so that government will protect their rights.

- If a government does not protect the rights its citizens, then they can and should change the government or start a new one.

BUT consider the following:

- Thomas Jefferson and many of the other Founding Fathers owned slaves.

- Slavery was still legal and enforced in all 13 colonies when the Declaration was signed.

- Most countries in Europe were ruled by Kings who believed they were given their power directly from God, and could rule however they wanted.

- Britain and the American colonies did have elections, but only wealthy men could vote or hold political office. Women and poor men did not have any political rights.

Pretend you live during 1776, and you have just read the Declaration of Independence.

Write a brief diary journal from the point of view of: (pick any three)

|

|

Comments and feedback welcome!